How and when you get your fats, carbohydrates, and protein every day can have a big impact on your ability to improve your physique. But when muscle building, strength development, and body-composition improvements are the goal, protein has a special significance. So why is protein surrounded by so many myths and bad information?

If you’ve ever eavesdropped on a bunch of lifters for more than a few minutes, odds are that protein came up in conversation—and in particular, how they meet their daily protein requirements.

They also probably said things like this:

- You need 1 gram of protein per pound per day.

- You need to get your protein every two hours.

- Your body can only absorb about 20 grams of protein per meal.

- You have to get your protein inside the “anabolic window” which slams shut shortly after you work out.

- Whey is the best form of protein, everything else is just an impostor.

Sometimes something sounds right just because it’s been repeated so often. But that doesn’t mean it is right. Here’s where each of these protein myths go wrong.

1. How Much Protein You Need Depends on Your Goals

Your daily protein requirement depends on whether you’re in a calorie deficit to lose fat or a calorie surplus to gain size. But the research definitely doesn’t say “more to grow, less to cut.” The opposite is true!

If you’re dieting, you need to consume more protein to minimize muscle loss, keep yourself feeling full to stave off hunger, and lose more fat. Research suggests that a range of 0.8-1.4 grams of protein per pound of body weight per day is the most effective amount to preserve lean body mass when you’re cutting.[1] The overall consensus for all athletes eating for maintenance or in a caloric surplus is to consume 0.5-0.9 grams of protein per pound.[2]

Factors such as your age, how conditioned you are to strength training, and what sport and activities you participate in affect where within these daily protein ranges you need to aim. For example, aging increases protein needs and people who have done more strength training actually require less protein.

In short, no one-size protein requirement is right for everyone. And more isn’t always better. It may just be…more.

2. You Don’t Need Protein Every 2-3 Hours

No, you don’t need to consume protein every two hours. Researchers have looked at the activation of muscle-building signals in response to protein ingestion. But these early studies were done with resting subjects, and their signals to stimulate muscle growth returned to baseline around 180 minutes after the subjects consumed protein.[3]

This measurement of the time after protein ingestion, known as the “muscle full” effect, gave rise to the idea that if you’re chasing gains, you have to continually top up your protein intake to keep those muscle-building signals flowing.

More recent research has shown that resistance training delays the “muscle full” effect for up to 24-hours after a workout.[4] This means that the protein you consume all day, not just within a few hours of your workout, plays a role in your hypertrophy.[5]

In terms of when you plan your meals, evidence suggests that eating six or more meals a day doesn’t produce demonstrably superior results or dramatically boost the availability of protein to your body.[6]

3. Think in Terms of Total Leucine, Not Total Protein

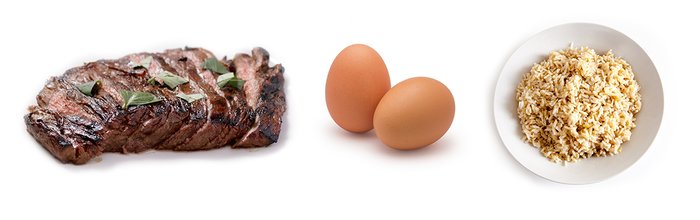

The idea that the human body can absorb only about 20 grams of protein per meal was based on research about whey and egg proteins. The body is able to absorb these two specific forms of protein very rapidly, so consuming 20 grams of these proteins per meal causes maximum stimulation of muscle proteins.[7,8]

The results of this research led to the suggestion that, because muscle proteins were maximally stimulated with 20 grams of protein, there was no benefit to consuming more and 20 grams constituted a ceiling for protein consumption.

We know now that the reason 20 grams led to maximum muscle stimulation was because whey and egg proteins are rich in the amino acid leucine, which is directly responsible for switching on anabolic muscle protein signals. The 20 grams of these proteins yielded about 1.8 grams of leucine, which turns out to be the real limit.[5]

To get 1.8 grams of leucine from lean beef, you’d need to eat 113 grams, which would include a total of 30 grams of protein. If you prefer brown rice protein, you’d have to eat about 48 grams of it to get your leucine quota.[9,10] In short, the limit of how much protein you could or should eat has more to do with how much of that protein it takes to get 1.8 grams of leucine, not how much actual protein you eat.

4. Take Your Time Climbing Through the Anabolic Window

The idea that you have to chug your protein shake before you’ve hit the shower is another myth that, once dispelled, will make your life easier. The so-called “anabolic window” is really pretty big—big enough for you to finish your workout, take your shower, make your way home, and eat a whole-food meal.

Research shows that muscle protein activation peaks within 1-2 hours after resistance training. Whether you consume your protein immediately after your workout or within a couple of hours, the anabolic response will be roughly the same.[11]

To maximize the hypertrophic signals that protein trigger, eat a meal containing 30-45 grams of protein three hours before your workout, then consume a leucine-rich meal or supplement up to three hours after.[6] Turns out that when you do resistance training, the “anabolic window” is almost like an “anabolic day.” You’ve got plenty of time to get your macros, so don’t stress out about it.

5. Whey Is Great Protein, But Not Necessarily the Best

When it comes to the quality of a protein, it goes back to the amount of leucine the protein contains. The research that led people to conclude whey was superior to other forms of protein was comparing the same absolute dose of each. When the researchers compared the amount of leucine in 20 grams of whey versus 20 grams of brown rice protein, whey got higher marks because it has more leucine per gram, but that doesn’t mean it’s the best or only way to get it.[5]

Researchers then looked at the amount of leucine in different proteins, instead of the amount of protein. They found that the activation of muscle-building signals was the same between different types of protein once the threshold of 1.8-2 grams of leucine was reached.[5] The researchers found, for example, that it takes 48 grams of rice protein or 25 grams of pea protein to yield the same 1.8 grams of leucine you can get from 20 grams of whey.[10,12]

Whey might contain a high concentration of leucine, but you can still get all the leucine you need from other proteins, you just might have to eat more. If you’re following a plant-based diet, or if you find that whey causes you intestinal distress (or just olfactory distress to those sitting around you), you lose nothing by opting for a plant-based protein such as pea protein. It will take 25 grams of pea protein rather than 20 grams of whey to get your leucine dose, but you’ll get it all the same.[13]

References

- Jäger, R., Kerksick, C. M., Campbell, B. I., Cribb, P. J., Wells, S. D., Skwiat, T. M., … & Smith-Ryan, A. E. (2017). International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: protein and exercise. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14(1), 20.

- Phillips, S. and Van Loon, L. (2011). Dietary protein for athletes: From requirements to optimum adaptation. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(sup1), pp.S29-S38

- Phillips, S. (2012). Dietary protein requirements and adaptive advantages in athletes. British Journal of Nutrition, 108(S2), pp.S158-S167.

- Atherton, P., Etheridge, T., Watt, P., Wilkinson, D., Selby, A., Rankin, D., Smith, K. and Rennie, M. (2010). Muscle full effect after oral protein: time-dependent concordance and discordance between human muscle protein synthesis and mTORC1 signaling. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 92(5), pp.1080-1088.

- Atherton, P. and Smith, K. (2012). Muscle protein synthesis in response to nutrition and exercise. The Journal of Physiology, 590(5), pp.1049-1057.

- Reidy, P. and Rasmussen, B. (2016). Role of Ingested Amino Acids and Protein in the Promotion of Resistance Exercise-Induced Muscle Protein Anabolism. Journal of Nutrition, 146(2), pp.155-183.

- Schoenfeld, B., Aragon, A. and Krieger, J. (2013). The effect of protein timing on muscle strength and hypertrophy: a meta-analysis. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 10(1), p.53.

- Witard, O., Jackman, S., Breen, L., Smith, K., Selby, A. and Tipton, K. (2013). Myofibrillar muscle protein synthesis rates subsequent to a meal in response to increasing doses of whey protein at rest and after resistance exercise. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 99(1), pp.86-95.

- Moore, D., Robinson, M., Fry, J., Tang, J., Glover, E., Wilkinson, S., Prior, T., Tarnopolsky, M. and Phillips, S. (2008). Ingested protein dose response of muscle and albumin protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young men. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89(1), pp.161-168.

- Symons, B., Sheffield-Moore, M., Wolfe, R. and Paddon-Jones, D. (2009). Moderating the portion size of a protein-rich meal improves anabolic efficiency in young and elderly. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(9), pp.1582-1586.

- Joy, J., Lowery, R., Wilson, J., Purpura, M., De Souza, E., Wilson, S., Kalman, D., Dudeck, J. and Jager, R. (2013). The effects of 8 weeks of whey or rice protein supplementation on body composition and exercise performance. Nutrition Journal, 12(1), p.86.

- Rasmussen, B., Tipton, K., Miller, S., Wolf, S. and Wolfe, R. (2000). An oral essential amino acid-carbohydrate supplement enhances muscle protein anabolism after resistance exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 88, pp.386-92.

- Babault, N., Paâzis, C., Deley, G., Guãcrin-Deremaux, L., Saniez, M., Lefranc-Millot, C. and Allaert, F. (2015). Pea proteins oral supplementation promotes muscle thickness gains during resistance training: a double-blind, randomized, Placebo-controlled clinical trial vs. Whey protein. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 12(1), p.3.